Recently, some exciting studies have thrown doubt on widely-held conventional assumptions about so-called human nature. Though philosophy, anthropology and psychology are the classic disciplines traditionally tasked with such investigation, an invigorating infusion of exciting new data comes from within the fields of biology, economics, mathematics and computer science.

One such idea that is long overdue—and the crux of social justice movements since time immemorial—is that selfishness is learned.

How many times have we all had to reckon with the conventional argument that human nature is inherently self-interested and greedy? This sentiment has been at the bedrock of defending the greed-is-good consumerism of modern capitalism and the rugged individualism inherent in the idea of the American dream.

After the fall of the Soviet Union in the early ‘90s, socialist and communist ideas seemed to have been trounced by the prevailing global empire of capitalism led by the United States.

Throughout the rest of the 1990s, anticapitalist organizers in the U.S. did manage to organize in resistance to the Gulf War—in reaction to the devastating impacts of neoliberal globalization a la NAFTA, in response to the HIV/AIDS crisis and in furthering the rights of the LGBTQ+ communities. However, in terms of organizing to create alternative economic relationships based upon cooperation rather than self-interest and competition, the U.S. left seemed to be at an impasse.

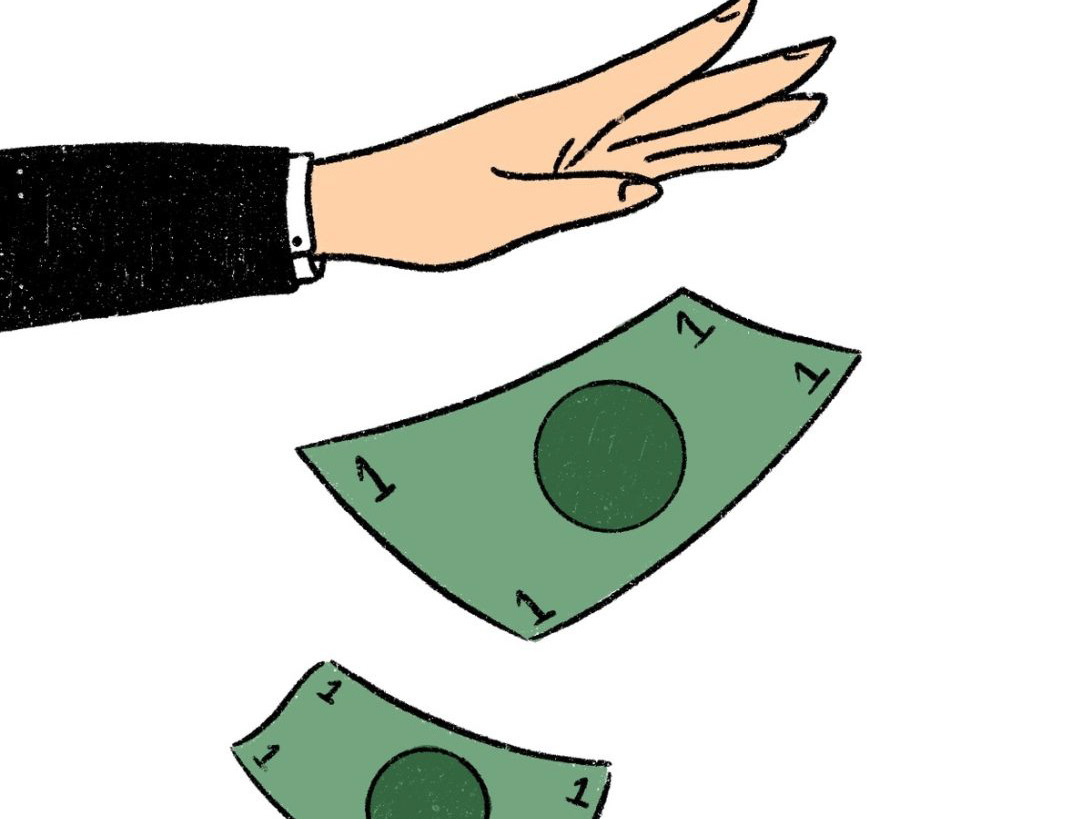

That is, until the Occupy Wall Street Movement was sparked in response to the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-2008. Cartoonishly greedy financial de-regulation by bankers and stock brokers had resulted in the biggest economic disaster since the Great Depression of the 1930s. Once again, the assumptions undergirding capitalism came under scrutiny by a growing segment of the population, both nationally and abroad.

While Occupy fizzled out after a short while, the conversations and ideas that it brought to the fore have only magnified. A Gallup poll from 2018 showed findings that less than 45% of young people in the U.S. found capitalism favorable.

Now, two years into a global pandemic, we are all forced to witness as supply chains break, as we watch our governments fail to keep us safe and housed, as they prioritize the economy and staying open above public health in spite of surging COVID-19 cases. We have also hardly been able to avert our eyes as the world’s 10 richest men collectively got $1.5 trillion—yes, trillion—richer during that same pandemic while the vast majority of us have suffered. Some of them even went to space to flaunt it at us.

It is in the wake of all of this that refreshing ideas and novel approaches to the problems of inequality are a welcome respite. Much like what has happened with the lies inherent to climate science denialism, maybe if we can break apart the propaganda and mythologies that our society and systems pass onto us as unquestionable fact, we can open to beautiful new horizons.

Again, we aren’t born selfish. According to studies gleaned from 10 different experiments by David Rand and his colleagues at Yale University, when people rely more on their intuition, it increases cooperation. By contrast, strict self-interest is elevated the more time is spent weighing the cost-benefits analysis of a given situation.

Importantly, challenges to the idea that we are inherently selfish are not really all that new. In his seminal pamphlet, An Anarchist Programme, the late 19th-century Italian anarchist Ericco Malatesta wrote, “We believe that most of the ills that afflict mankind stem from a bad social organization and that man could destroy them if he wished and knew how.”

The crux of his argument was that social structures condition people to develop in certain ways independent of their will or intentions. These structures often just bring out the worst in people because they are designed to do so. He offered the solution that in order to change society, we would have to change the social structures themselves rather than the simplistic and individualized conventional thinking that says we can just replace bad rulers with good rulers, or reform bad individual behaviors while leaving the system itself intact.

“Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely,” stated fully in 1887 by Lord John Acton. “Great men are almost always bad men.”

Rather than focusing on rotten individuals who invoke our ire, we should be prefigurative, building new ways of being that replace these selfish and individualist modes of being in the here and now. Societal systems reproduce themselves through repeated behaviors and customs—and their influence on the kinds of people that emerge from them.

If we want a world based on egalitarian cooperation, we are going to have to completely change ourselves and the structural systems around us—and, in doing so, create the conditions for new and evolving ways of relating socially and economically.

We can look to another old, bearded philosopher, Peter Kropotkin, for inspiring and scientifically-informed ideas on human cooperation. His scholarship and theories robustly countered the prevailing notions of his time, namely those of Social Darwinism, which can concisely be summarized as “survival of the fittest.” Darwin himself was not a proponent of this unscientific application of his evolutionary theory of biology.

It was Kropotkin who coined the now-ubiquitous phrase mutual aid in the treatise of the same name. In it, he challenged the prevailing Hobbesian procapitalist worldview—namely that human nature is motivated by aggressive impulses and is intrinsically selfish, competitive and possessive. Kropotkin did not deny the realities of conflict, competition and egoism. Rather, he proposed that cooperation, mutual support and care are also widely expressed in the animal kingdom and in all human societies throughout history.

In fact, these ideas are even older than Kropotkin or Malatesta—or even Karl Marx. The principles of horizontally-structured societies based upon collectivism and cooperation are as old as the human species, and have been and are still present in many societies across the globe.

In the Pacific Northwest, many Indigenous peoples organized their whole societies around potlatches, which were gift-giving and sharing feasts. We owe them, and this tradition, for the English word potluck. On the other side of the continental U.S., the Haudenosaunee Confederacy—more widely known as the Iroquois Confederacy—held all lands in common, practiced self-management of work tasks and did not believe in private property.

There are many other examples of communalist, cooperative societies flourishing prior to the rise of capitalism and colonialism. And there are many books that you can—and should—read about the subject such as The Dawn of Everything by the late David Graeber, Worshiping Power by Peter Gelderloos, Society Against the State by Pierre Clastres and The Art of Not Being Governed by James C. Scott, just to name a few of my favorites.

We can look to our own collective histories for inspiration, but we can also look to the findings of science for affirmation of wider possibilities than the current paradigm allows. In all of these, we will find that human beings are not predestined or stuck in this deterministic trap. We are not inherently mechanistic, self-interested or merely individuals competing for riches in a winner-take-all bloodbath.

There are many forces that transpire to create the conditions in which we emerge. It is incumbent upon us to transform these and ourselves in the pursuit of human flourishing and development. All human beings, by virtue of existing, have an inalienable right to all that they need to survive, thrive and prosper. Don’t let anyone tell you otherwise.

Illustration by Whitney Griffin